I guess I knew about Brian all along. Although he is five years older, we have always been close and never really had a problem hanging out. I’ve always looked up to him. He was always so collected and cool. Everybody wanted to be around him. Well, that was until everybody found out about him. They stopped calling him or inviting him out to parties. Some of them have even stopped talking to him and do not want to go anywhere near him. It’s like he had a contagious disease. I even overheard someone say that it was a psychological problem – like he was wrongly programmed when he was born. They began viewing him as something unnatural. An alien. I don’t know who found it harder to believe. The girls who were in denial or the boys who were, well, scared. But boys have a weird way of showing their emotions. When they feel threatened either because someone is out to get them or they are worried about their reputations and egos, boys tend to strike out first. They strike out so that they are not the ones being struck. And that’s what happened.

It was a warm, sunny June afternoon. The room was plastered with posters of guitars and hockey players. In the corner was a large, pine shelf filled with trophies, books, magazines all dedicated to the sport. A bed dressed in green sat still and solemnly next to a tiny tool box. On the surface of the rusty tool box was a shadow that followed the still, hanging body; a muscular and defined yet silent body. It wore the school’s hockey team uniform: green shirt, white shorts and socks with deep green football boots. Its head held a somewhat peaceful expression. It said this much: I accept what had happened. The room was reluctant but faithful to its late owner and staged his last appearance. The secretive silence then unwrapped itself into a piercing scream. And with the scream, like Pandora’s Box, hell’s sorrow flooded the rest of the house.

They started by name-calling and shoving him down the corridor. They stuck pictures and pink glitter on his locker door. They refused to use the same showers after a practice session. These were the friends of Brian. Admirers are now finger-pointers, gossipers. Brian took it all in. He never said a word. He only smiled. When I asked him if he wanted to talk, all he ever did was smile. He never cried in front of me but I heard him several times in the dark. My room was right next to his. We used to play this game where after dark, after our parents had gone to sleep, we’d stay up most of the night talking into the wall. We’d use two plastic cups and speak into them. The cups had long been thrown out by Mum. But even without the cups, I heard the mousey sobs, whispering silent pleads to the night sky.

There is also something else funny about boys. When their target doesn’t respond, they aggregate their actions. It is almost as if the lack of reaction is an encouragement. Very soon, apple cores were thrown at Brian and cheap makeup spread across our front door while hate mail made its way into our letter box. My parents began to question. Brian and I had never told them much about school. They wouldn’t have understood anyway. Dad made a few phone calls and visits to school and everything became quiet for a while. Gradually, some people began talking to him again. I saw one or two girls linking arms with him a few times. Even Mum seemed to have quietly accepted the truth and started to do his laundry again. Time was moving forward and it carried us.

Amongst the mess on the working desk were two envelopes, both with the audience’s names written carefully and neatly in capital letters. They held their ground faithfully on the spot for almost two weeks before they were finally noticed. It was, however, another three days before they were read, revealing the reasons and the legacy left behind. One of them camouflages with a pile of other documents in a chest of drawers. The chest of drawers gathers dust over the years in a mute corner of the loft. The other had been framed and lives on the wall in a small apartment in the city, not very far from its sibling’s dwelling place.

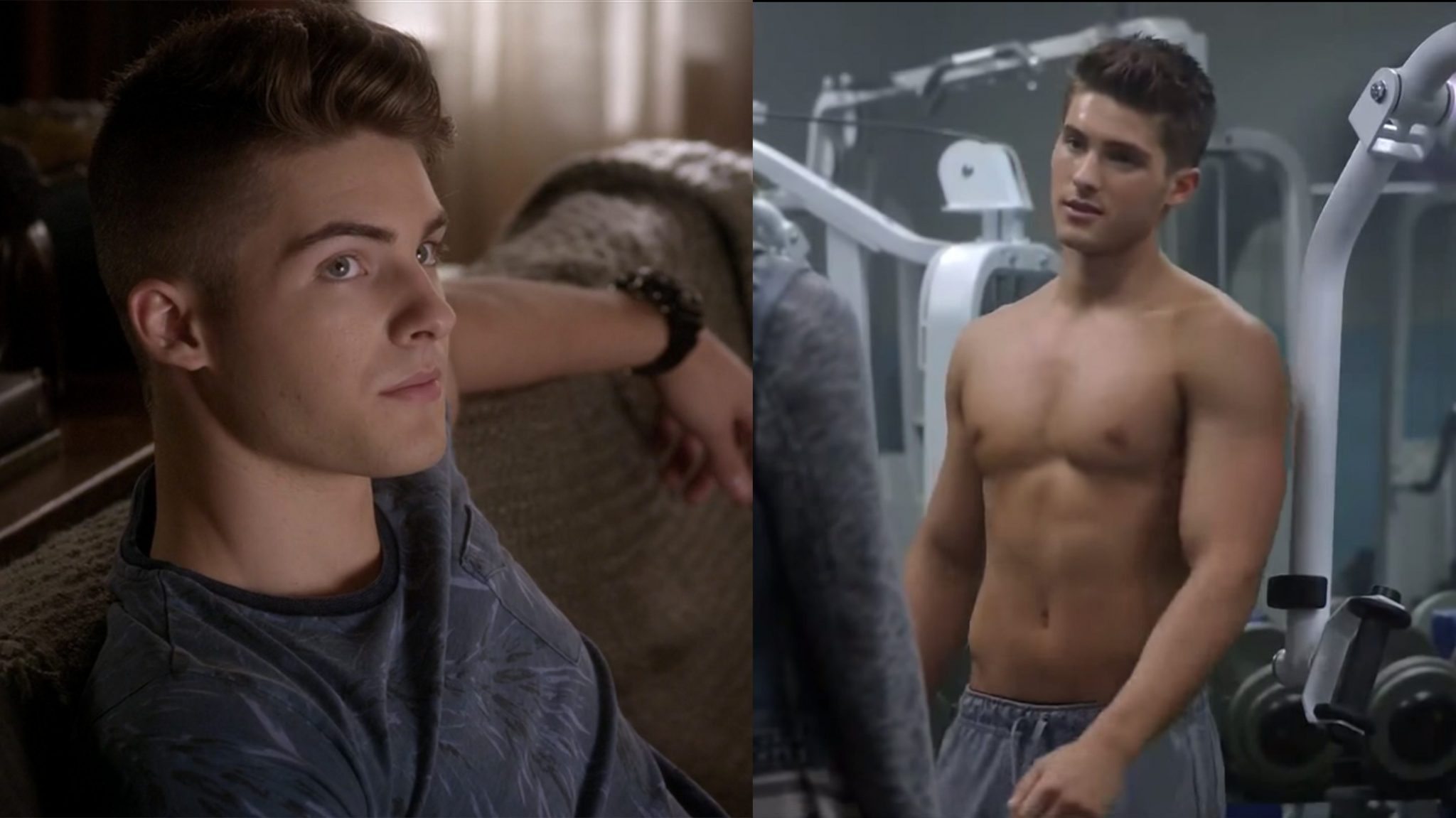

I remember the first time Brian brought Samuel home. Brian had told me so much about him already but nothing was better than meeting the tall, slim, blonde-haired apprentice journalist. He had a trademark of freshly washed dark coloured woollen jumpers over clean-cut pastel shirts and grey jeans. He wore a pair of pale green Converse sneakers and had a cluster of black stars tattooed on his right wrist. They had met through a confidence-building camp the school social worker arranged for the local schools. I had never seen Brian happier and it made me happy, too. Samuel gave us each a present. Mine was his latest unpublished article. He was always positive and believed in a world of tolerance, understanding and acceptance. He had an air of majesty that demanded respect. Everything he said cast a spell on any listening ear.

They had been together for almost a year when Samuel came to our house. Brian had moved in with Samuel almost immediately after telling our parents. It didn’t bother Samuel’s parents because they had long disowned him. Samuel lived in a council flat near the upper market. I often asked if I could visit but Brian didn’t want me to get into trouble.

It took me a long time to get used to walking to school on my own.

A police inquest was made and concluded quickly. Even without the letters, the motives were obvious. The brief brush of evidence was done more out of duty than care. No one really wanted to know the truth. The truth is held tightly by two pieces of thin glass, encased by four simple pieces of wooden stripes. And with it, the complex and mixed emotions ignored by the blind inquest.

I remember, very well, how it all unfolded. It was only after my scream that things rushed forward into an unrecognisable blur. I forgot everything that happened afterwards and it didn’t matter. My mind is permanently engraved with the fateful sight. But I guess I knew all along about Brian and what he would do or say.

There never was a Samuel. I think that’s what would have happened; I know Brian.